China-Russia Dashboard: Facts and figures on a special relationship

China-Russia Dashboard: a special relationship in facts and figures

Sino-Russian relations are closer today than they have been in decades. In these times of historic geopolitical tensions, it is all the more important to understand the nature and elements of the relationship of two of the world’s most influential powers. This dashboard aims to contribute to a better understanding by tracking and analyzing the economic, political, security, and societal dimensions of China-Russia relations and their changing quality over time. It is a collaborative research effort of the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW), the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), and the Swedish National China Centre (NKK) and Stockholm Centre for Eastern European Studies (SCEEUS) at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs (UI).

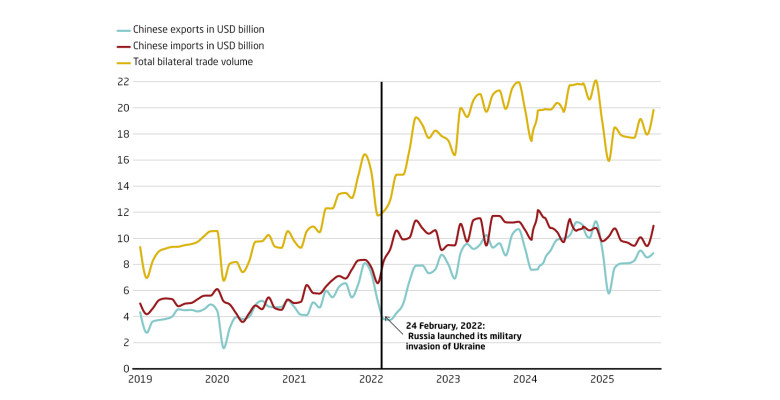

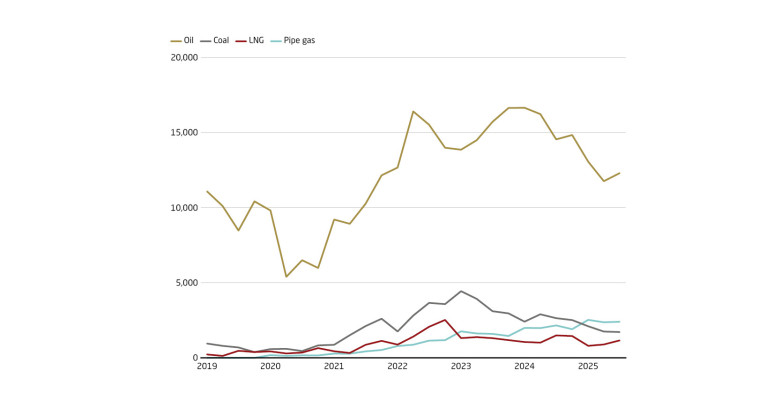

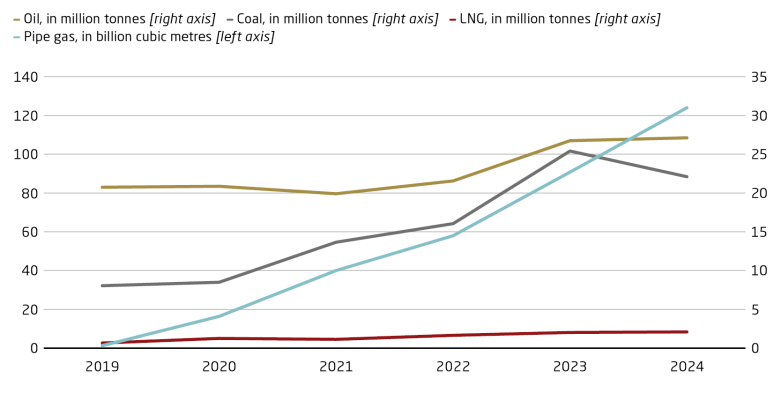

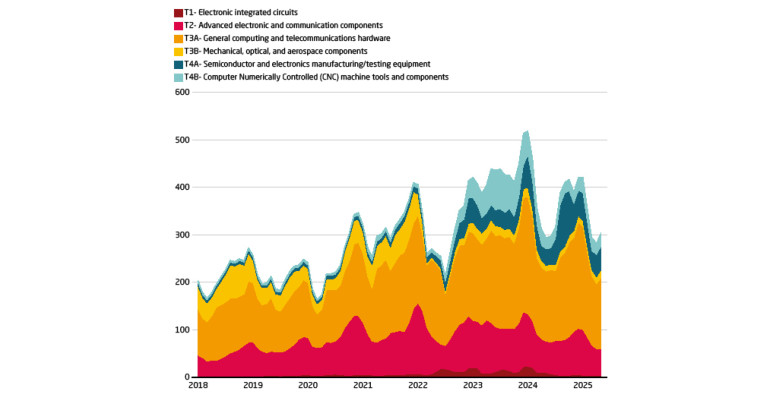

Economics

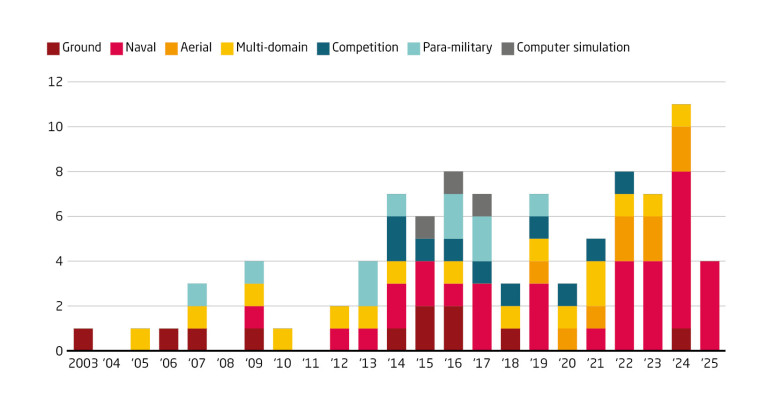

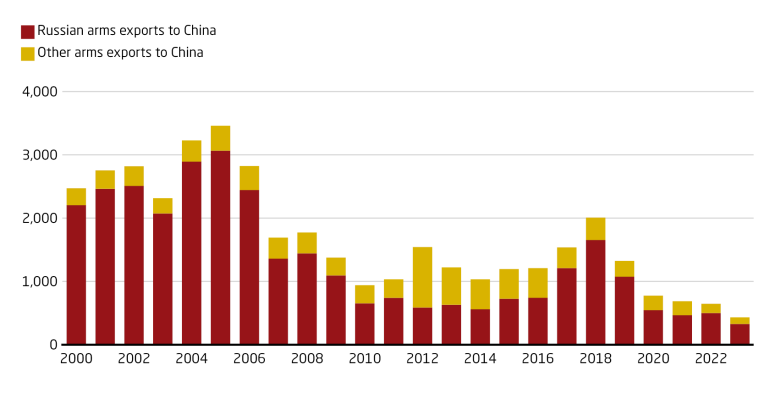

Security

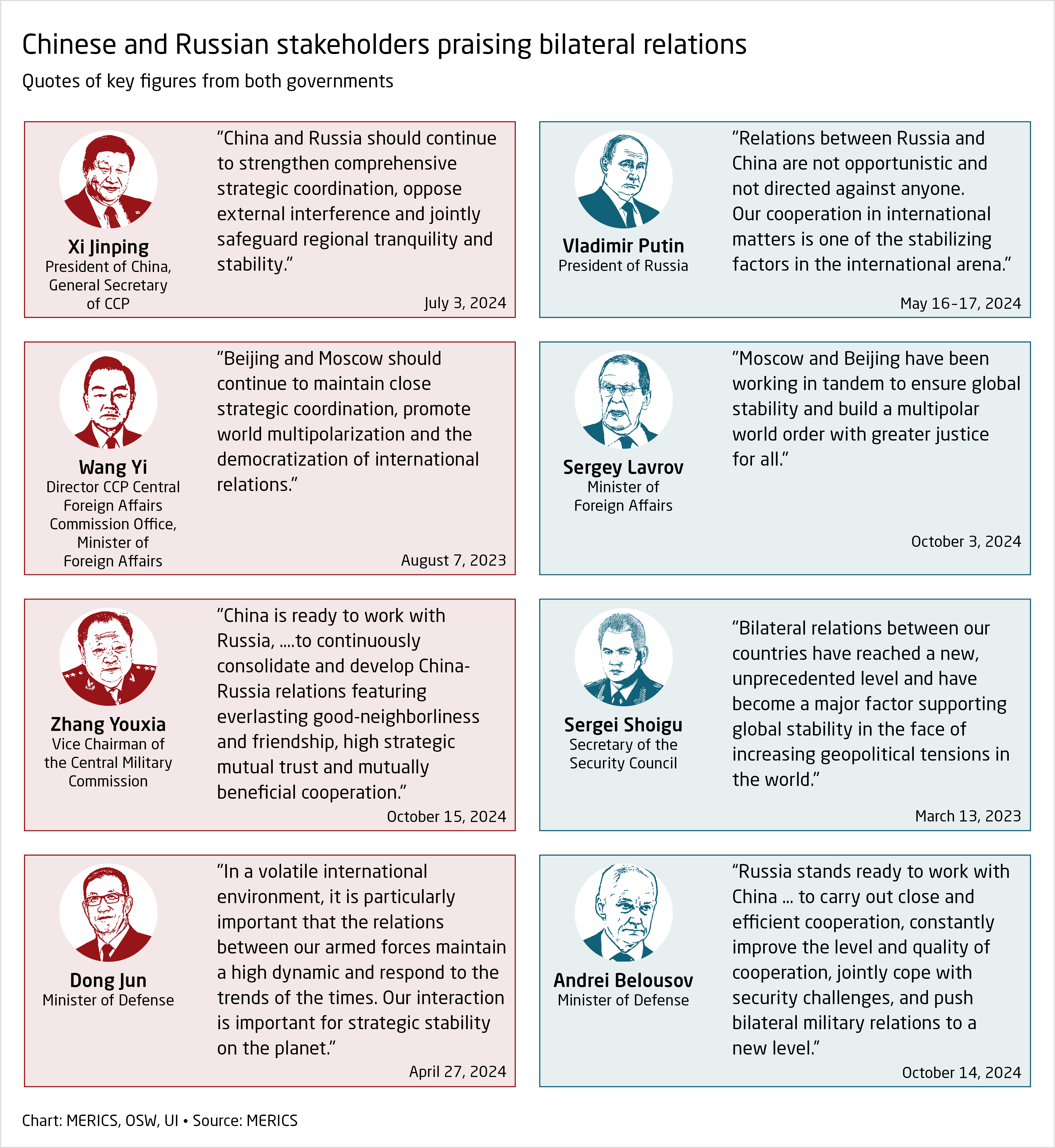

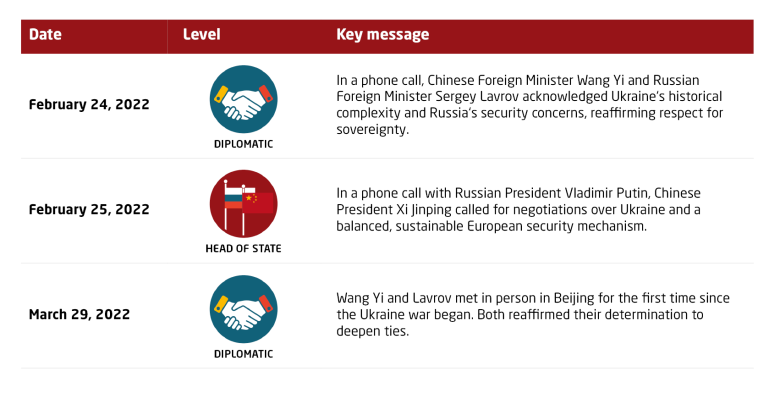

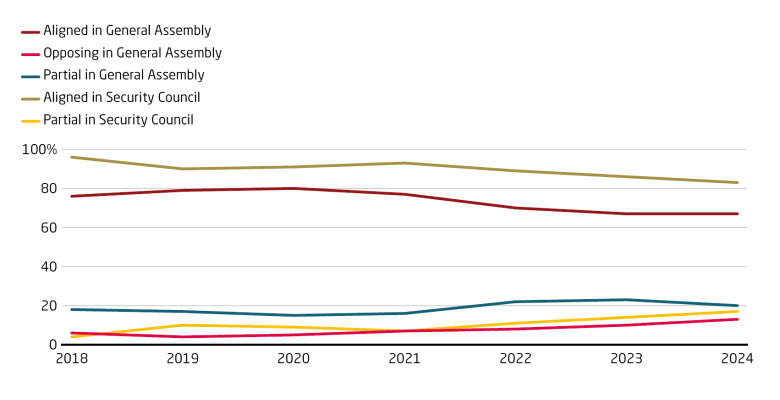

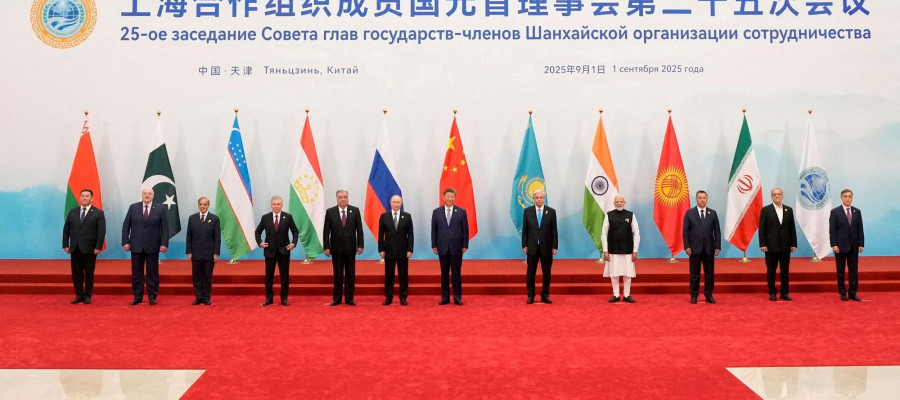

Politics

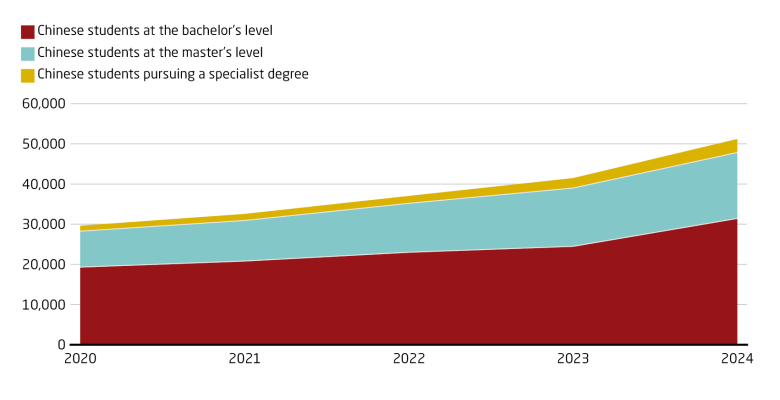

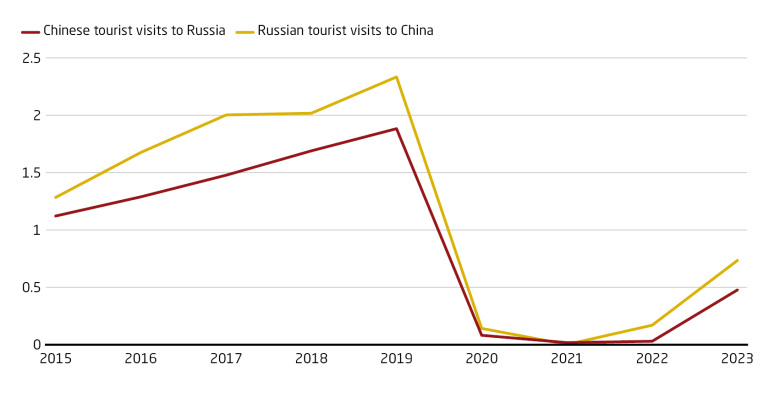

Society

Analyses

Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS)

Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW)

Swedish Institute of International Affairs (UI)